What Gerola Saw — and What We Will Never See Again

The story of one church from Giuseppe Gerola’s monumental catalog.

More than 120 years ago, the Italian historian and researcher Giuseppe Gerola traveled across Crete on a mission commissioned by the Italian government. His task was to document the Venetian presence on the island. In two years he collected a massive photographic archive, which later became the backbone of his monumental work "Monumenti venetti nell’isola di Creta.” Preparing and publishing this material took him nearly thirty years. In that time, some of the monuments he described disappeared completely — destroyed either by natural disasters or human hands. All that remained of them was a memory and, sometimes, a single photograph. For this church, Gerola wrote only two words: ora distrutto — “now destroyed.” Nothing more.

For the last several weeks, ever since a reproduction of "Monumenti venetti" landed in my hands, I’ve been completely absorbed in deciphering and analyzing the photographs. I search for the places Gerola described, mark the churches on the map, and travel with him — page by page, valley by valley.

Today I want to take you to one of those places. I want to show you something unique, forgotten, and no longer existing. Let’s take a small journey through time. Let’s resurrect a moment. Let’s walk, just for a while, in Gerola’s footsteps.

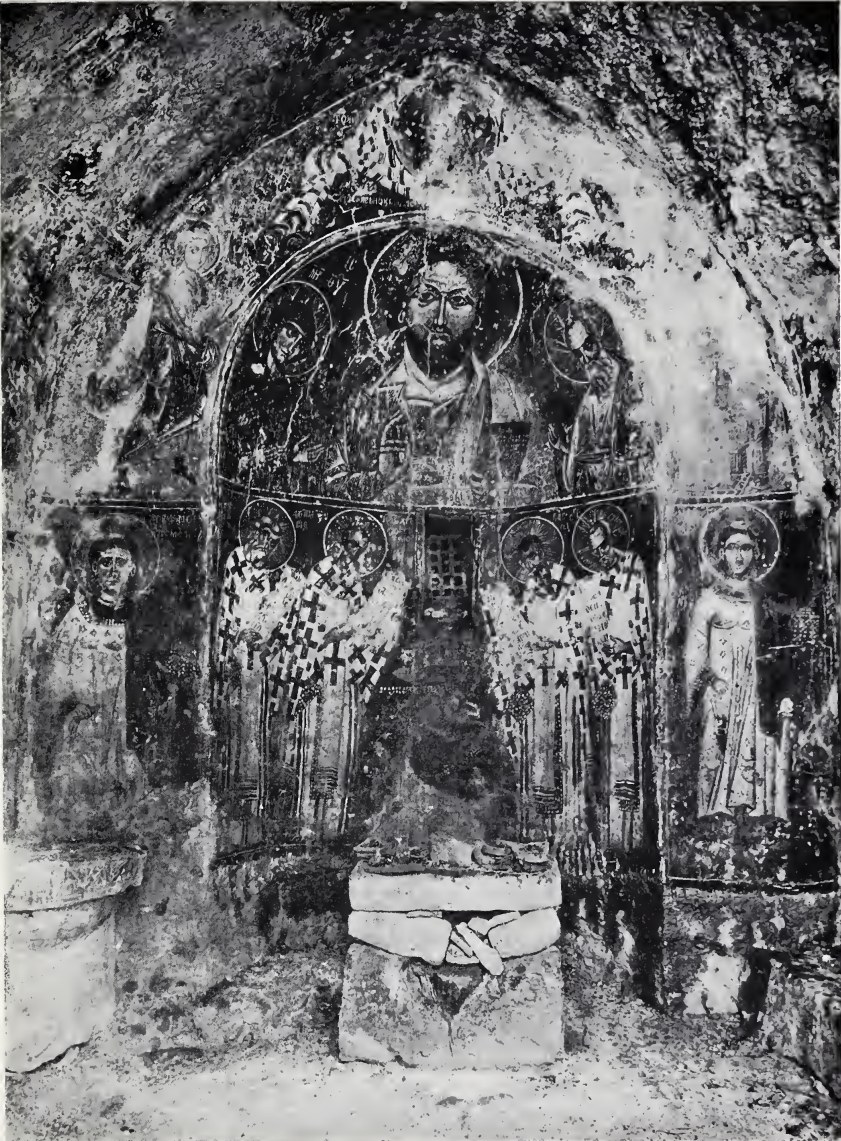

Hidden deep in the overgrown valley of Spili, far from fountains and modern tavernas, once stood a church that today appears on no map. Only one photograph remains — number 624. One single line in Gerola’s catalog: “Apse frescoes of the church of Saint John, depicting deacons and hierarchs, the bust of Christ between Mary and John, the Annunciation, and the Shroud.” And that is enough.

If you had turned off the main road over a century ago and descended toward the olive grove, passing three wells and a low wall of fieldstones, you would have found it. A small one-aisled church, with a southern entrance shaded by a fig tree. Unassuming on the outside, as if reluctant to disturb the world around it.

Inside… a mystery. In the apse, just above the altar, a row of holy deacons and bishops. Holding the Gospel, wearing the omophorion, their hands raised in prayer. Bearded faces, elongated, their gaze fixed not on the viewer but somewhere beyond time. Above them — the bust of Christ. Not triumphant, but present. On either side: Mary and John, in the Deesis arrangement. They do not plead; they remain.

Higher still — the Annunciation. Gabriel caught in mid-motion. Mary, not yet Mother, but no longer just a girl. She turns slightly, as if recognizing something quietly, almost reluctantly. A moment of tension. The world holds its breath.

And the Shroud. We do not know whether it appeared as an Epitaphios or as a symbolic reference to the burial. But it was there. Perhaps between the columns, perhaps by the entrance to the sanctuary. In the half-light of prayer and the warm dust of ochre.

Gerola does not mention a founding inscription. Perhaps it never existed. Perhaps time had already erased it. But the names of the saints were surely written above their heads. Maybe a donor was depicted there — a monk, a family, a villager. No one knows anymore.

The church is gone. No doorway, no fig tree, no apse. Perhaps it collapsed during wartime. Perhaps it simply faded away, as memories vanish into collective silence. No one speaks of it. No signpost leads to it. Only one photograph remains.

Yet through that photograph — thin as the veil of the Shroud — something more than an image passes through. An intention. A belief that holiness is not a matter of size or grandeur, but of presence. That even a tiny, forgotten chapel can be a ladder to heaven.

So let it be — a small resurrection. Imagine you are there now. In Spili. With Gerola’s map in hand. Dusty, tired. And suddenly, on your left, behind a wild rose bush, you notice a fragment of wall. Red plaster. And something else — a carved letter, maybe “ΙΩ”… perhaps Ioannis.