Elafonisi Beach, a Place That Deceives

The beauty of this landscape easily drowns out the fact that it was a witness to events closer to Greek tragedy than to a holiday story.

When you drive to Elafonisi on a clear day—exactly the kind of Cretan weather locals associate with Easter—it is hard to believe that this place carries the weight of history. The air smells of roasted lamb, sun-warmed earth, and that particular calm that comes after a church service, when families return home and children still run around in their festive clothes. The sea is turquoise, almost unreal. The sand has a pink hue that looks more like a photographic filter than a natural phenomenon. Everything seems to say: this is paradise.

And that is precisely why Elafonisi deceives so easily.

Because beneath this postcard image lies the memory of a place that witnessed events more fitting for a Greek tragedy than for a travel brochure. On Easter of 1824—a day which in the Christian calendar speaks of passage, salvation, and a new beginning—this now tranquil place became the scene of a massacre that still resonates in western Crete.

Imagine a morning almost identical to the one you can see today. The sun rises over the lagoon, the wind is gentle, the sea calm. Except that instead of towels and parasols there are people fleeing in silence, trying not to reveal their presence. The Greek War of Independence is underway, and Crete—as so often in its history—takes part with hope, but without illusions. In the regions of Kissamos and Selino, news spreads of approaching units under Hüseyin Bey, Albanian soldiers sent to the island on the orders of Muhammad Ali of Egypt. Their task was not to suppress resistance in a “military” sense. It was to break the backbone of an entire community through fear, brutality, and demonstrative cruelty.

Elafonisi was not a tourist destination then. It was a last resort. A small islet separated from the mainland by a shallow sandbar, treacherous even in good weather. A place that could be reached on foot only when the sea allowed it. And it was there that inhabitants of nearby villages fled: women, children, the elderly, and a small group of armed men meant to defend them. According to accounts, there were several hundred people. Some believed they might escape from Elafonisi to the Ionian Islands, beyond the reach of the Ottoman-Egyptian forces. Others simply hoped the island would give them a few days—time enough for something, anything, to happen that would allow them to survive.

Today you cross that sandbar effortlessly, feeling cool water and smooth shells beneath your feet. In 1824, the same passage was the boundary between hope and panic. Accounts say that the first attackers struggled to force their way across the narrow stretch of water. Horses slipped on the stones, cavalry lost momentum. For a moment, the defenders believed the sea might stand on their side. But the size of the army and the determination of the attackers prevailed. After repeated attempts, the troops broke through to the island, and the fate of those hiding there was sealed.

After that, everything happened quickly and without mercy. Descriptions speak of desperate flight into the sea. The waves that today calmly reflect light in turquoise streaks became a trap for those who could not swim or who tried to save their children. Some people died in the water; others were killed on the spot—regardless of age. There is an account from the crew of a fishing boat who heard screams from the island but did not dare approach. Seeing Ottoman ships, they knew that offering help would mean their own death. The women and children who survived were taken captive. They ended up in slave markets in Egypt—a fact that can be hard for a modern reader to accept, but which in the nineteenth century was brutally commonplace.

The sources differ in their numbers. This is where an area of discrepancy begins, one that cannot be honestly resolved today. Some speak of several hundred victims; others give lower figures. One thing is common to all accounts: Elafonisi was a massacre, and it has been remembered as a massacre.

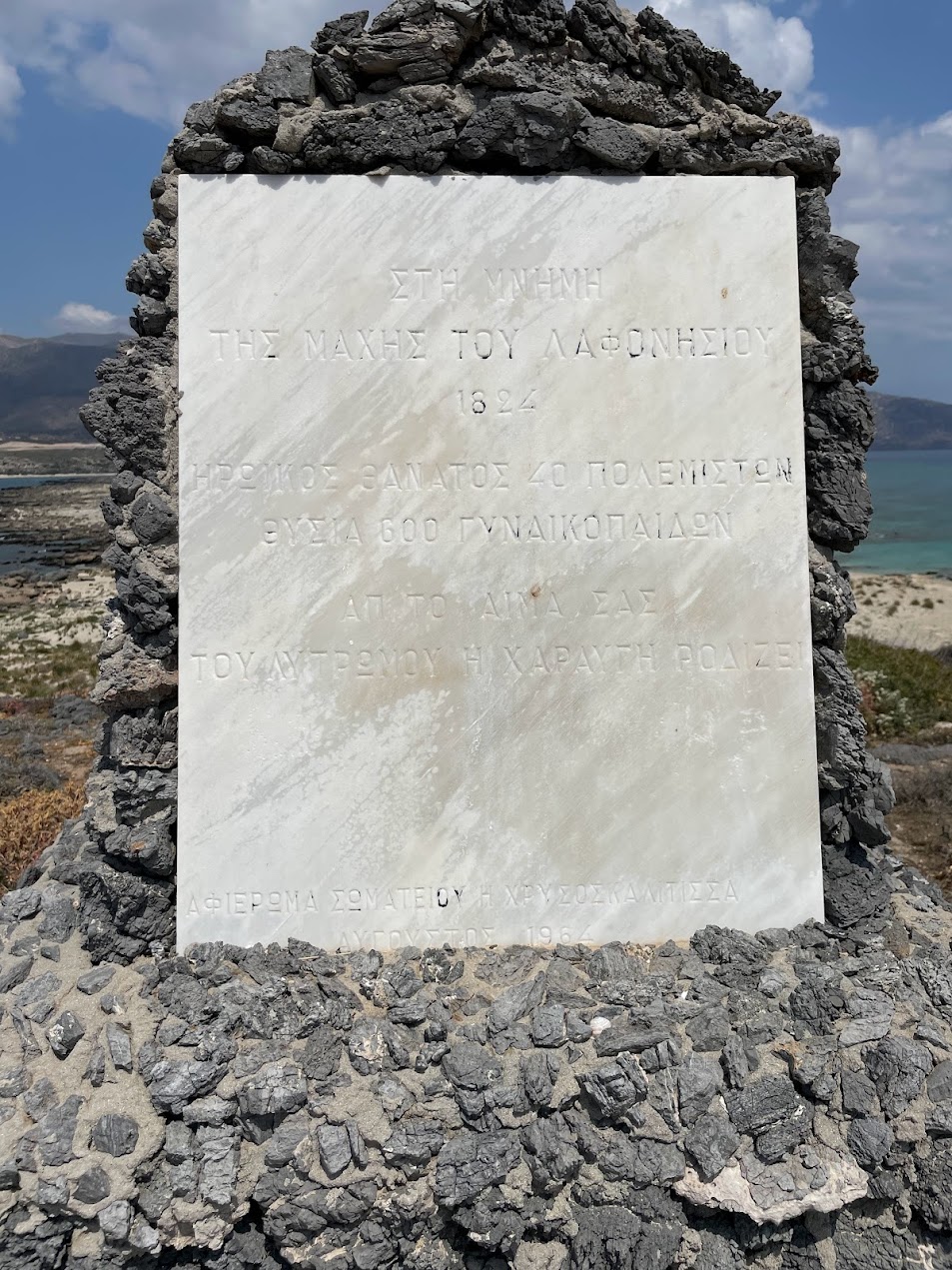

When you stand today at the highest point of the island, by the monument dedicated to the victims, the sea looks like a mirror. The silence can feel almost unnatural. It is hard to believe that this same place could become a collective grave for people who did not expect that the most important feast of the Christian calendar would turn into a day of absolute darkness. Cretans have not forgotten. Anniversaries are commemorated here regularly, and the events of 1824 function in local collective memory under the name “Lafonisia.”

That name leads further.

Because Elafonisi is not just a single episode. Forty-three years later, in 1867, another scene of Cretan resistance unfolded nearby: the sinking of the steamship Arkadi, which was transporting weapons and refugees during the next uprising. It was sunk on August 7—for some, an act of desperation; for others, proof that western Crete contains a particular concentration of history, where tragedy and resistance keep returning to the same places. As if geography itself were an accomplice to memory.

And only at the very end comes a reflection that seems lighter, yet is just as meaningful: the name. The official Ελαφονήσι means “Deer Island”—from eláfi (deer) and nisí (island). The etymology is simple, logical, linguistically sound. But in the speech of western Cretans, the forms Λαφονήσι and Λαφονήσια function just as naturally. Harsher, more local, rooted in dialect. These are the forms used during anniversaries and commemorations. Language betrays memory faster than monuments.

And “Treasure Island”? That is a modern story. A romantic legend about pirates who supposedly hid their loot here. It has no confirmation in etymology or in sources. But its very popularity says something: Elafonisi provokes the imagination, demands a narrative. People sense that this place carries more than just a pretty landscape.

So when today you walk barefoot on the pink sand, it is worth stopping for a moment. The sea still murmurs, the wind moves children’s footprints across the sand, tourists take photos. And yet Elafonisi is not just a “pretty beach.” It is an island that remembers. And if you give it a moment of attention, that memory can speak—quietly, but very clearly.